| |

No other area of the world suffered so great losses of Jewish life and culture to Nazi led terror as did the countries of Eastern Europe. Over 90% of Poland's three and one half million Jews perished in the Holocaust, in its ghettos, in its killing fields, on its death marches, and in its camps. Today Poland and the Czech Republic seek to find appropriate ways to honor the Jewish dead in an attempt to atone for their own complicity in the perpetration of the largest systematic murder in history that victimized their non-Jewish populations as well.

Below I have documented methods of memorialization at these concentration camps and death camps in Poland and the Czech Republic: Majdanek, Belzec, Auschwitz, Birkenau, and Plaszow in Poland; and the Terezin Gestapo Prison in the Czech Republic. Other places of Holocaust commemorization documented here deal with Ghetto sites and other places of memorialization in Warsaw and Krakow in Poland, the Jewish District of Prague, and the Theresienstadt Ghetto in the Czech Republic.

Jewish Ghettos were established by an order from Reinhard Heydrich on September 21, 1939, three weeks after the beginning of the war. This order made it the responsibility of a Nazi-appointed council of Jewish Elders to force their people into the ghettos. Jews were sent from small towns and villages by train. Transported in locked passenger cars, large numbers died on the journeys.

Jews were separated from the non-Jewish population first by barbed wire, then by walls impregnated with shards of glass. New arrivals were crowded into rooms with other families, and hundreds of thousands of Jews were forced to live in a space of a few city blocks. A Nazi report estimated that there were seven Jews living in every room in the Warsaw ghetto. In the first years, the most prevalent threat to life in the ghettos was starvation. Between 1940 and 1942 an estimated 100,000 Jews died of starvation and disease in the Warsaw Ghetto alone.

The first ghetto was set up in Piotrkow, Poland on 28th October 1939. The two largest ghettos were established in Warsaw and Lodz. Other main ghettos were set up in Krakow, Lublin, and Lvov. The ghettos were a preliminary step in the annihilation of the Jews, rather than just a method to isolate them from the rest of society. As the war against the Jews progressed, the ghettos became transition areas, used as collection points for deportation to death camps and concentration camps.

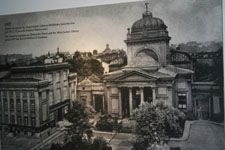

The Jewish Historical Institute is located in the building of the former Main Judaic Library, built during the years 1928 - 1936. The building housed library space, reading rooms and large auditorium and exhibition rooms. The structure harmoniously blended with the Great Synagogue adjacent to it, which had been built during the years 1876 - 1878. This pre-war picture of the Library and the Synagogue is on display at the Institute. The Jewish Historical Institute is located in the building of the former Main Judaic Library, built during the years 1928 - 1936. The building housed library space, reading rooms and large auditorium and exhibition rooms. The structure harmoniously blended with the Great Synagogue adjacent to it, which had been built during the years 1876 - 1878. This pre-war picture of the Library and the Synagogue is on display at the Institute.

The Jewish Historical Institute was founded with its main goal to save from oblivion both the history of the murder of Polish Jews, and the heritage of their eight centuries old culture and civilization. In 1946, there were 200,000 Jews living in Poland, only 6% of their prewar population of 3.5 million. Several waves of emigration after the war meant that about 95% of those Jews in Poland who had survived the Holocaust left the country. The Institute's role must thus be defined differently today than at the time of its foundation. The Jewish Historical Institute was founded with its main goal to save from oblivion both the history of the murder of Polish Jews, and the heritage of their eight centuries old culture and civilization. In 1946, there were 200,000 Jews living in Poland, only 6% of their prewar population of 3.5 million. Several waves of emigration after the war meant that about 95% of those Jews in Poland who had survived the Holocaust left the country. The Institute's role must thus be defined differently today than at the time of its foundation.

Currently, its mission is three-fold: First, it is a center to preserve documentary materials related to the Jewish historical presence in Poland, while also being a center for academic research, learning, and the dissemination of knowledge about the history of Jews in Poland. Second, it is an important bridge between the Polish-Jewish Diaspora and the land of their ancestors. More than half of the world's Jews today have roots in Poland. The Institute's third mission is linked to Poland's democratization and the spread of democratic values throughout Polish society by helping to reconstruct a true vision of Poland's past as a country in which Jews formed an integral part. The Institute has become a bridge to a historical consciousness in Polish society bringing it closer to a truer picture of Polish history. Director Feliks Tych affirms the "goal is to make the Institute an important and influential place of academic research and a permanent educational center providing information about the history and culture of the Polish Jews." Currently, its mission is three-fold: First, it is a center to preserve documentary materials related to the Jewish historical presence in Poland, while also being a center for academic research, learning, and the dissemination of knowledge about the history of Jews in Poland. Second, it is an important bridge between the Polish-Jewish Diaspora and the land of their ancestors. More than half of the world's Jews today have roots in Poland. The Institute's third mission is linked to Poland's democratization and the spread of democratic values throughout Polish society by helping to reconstruct a true vision of Poland's past as a country in which Jews formed an integral part. The Institute has become a bridge to a historical consciousness in Polish society bringing it closer to a truer picture of Polish history. Director Feliks Tych affirms the "goal is to make the Institute an important and influential place of academic research and a permanent educational center providing information about the history and culture of the Polish Jews."

An ironic turn of events in the middle and closing years of WWII fated the Institute into becoming the guardian of the richest collection of objects from Jewish culture that survived the Holocaust. When the residents of the Warsaw Ghetto began to be deported to the extermination center in Treblinka in July 1942, the Germans used the Institute building as a warehouse for looted items. After the squelching of the Warsaw Uprising on May 16, 1943, the Great Synagogue was destroyed by the Germans in retaliation, and the Institute was heavily damaged. (Site of the destroyed synagogue pictured above). In 1946, the Warsaw government gave the sites over to the Central Committee of Jews in Poland. The Committee, in conjunction with the Central Jewish Historical Commission, began hunting for and preserving material traces of Jewish past in the wreckage, while also collecting evidence of Nazi war crimes. All the materials collected were then stored in the renovated Jewish Historical Institute building. An ironic turn of events in the middle and closing years of WWII fated the Institute into becoming the guardian of the richest collection of objects from Jewish culture that survived the Holocaust. When the residents of the Warsaw Ghetto began to be deported to the extermination center in Treblinka in July 1942, the Germans used the Institute building as a warehouse for looted items. After the squelching of the Warsaw Uprising on May 16, 1943, the Great Synagogue was destroyed by the Germans in retaliation, and the Institute was heavily damaged. (Site of the destroyed synagogue pictured above). In 1946, the Warsaw government gave the sites over to the Central Committee of Jews in Poland. The Committee, in conjunction with the Central Jewish Historical Commission, began hunting for and preserving material traces of Jewish past in the wreckage, while also collecting evidence of Nazi war crimes. All the materials collected were then stored in the renovated Jewish Historical Institute building.

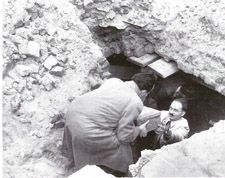

A particularly valuable part of the Institute's collections is the unique clandestine Warsaw Ghetto Archive, known by the name of the man who created it, the Ringelblum Archive. Emmanuel Ringelblum formed and directed a group whose main task was to document what life was like in the Warsaw Ghetto, the largest ghetto in occupied Europe. The secret archive was hidden on August 3, 1942 and then buried beneath the basement of a school in February 1943. Another set of materials was hidden the night before the ghetto uprising. Only the documents hidden beneath the school were recovered after the war. In all, there are an estimated 6,000 documents in the Ringelblum Archive - about 30,000 individual pieces of paper. A particularly valuable part of the Institute's collections is the unique clandestine Warsaw Ghetto Archive, known by the name of the man who created it, the Ringelblum Archive. Emmanuel Ringelblum formed and directed a group whose main task was to document what life was like in the Warsaw Ghetto, the largest ghetto in occupied Europe. The secret archive was hidden on August 3, 1942 and then buried beneath the basement of a school in February 1943. Another set of materials was hidden the night before the ghetto uprising. Only the documents hidden beneath the school were recovered after the war. In all, there are an estimated 6,000 documents in the Ringelblum Archive - about 30,000 individual pieces of paper.

The Institute's exhibit rooms on the second floor are dedicated to The Life, Struggle, and Destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto 1940-1943. The exhibition shows the Holocaust's successive stages in Warsaw, from the first anti-Jewish decrees of the German authorities, to the sealing of the ghetto, then the annihilation of nearly all its residents. The exhibition is for the most part based on materials from the Ringelblum Archive. Most of the display materials are photographs and documents - there are very few three-dimensional artifacts from the ghetto since most everything in the Jewish quarter was destroyed. Click here ---->Exhibit<.---- to view more from the exhibit. The Institute's exhibit rooms on the second floor are dedicated to The Life, Struggle, and Destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto 1940-1943. The exhibition shows the Holocaust's successive stages in Warsaw, from the first anti-Jewish decrees of the German authorities, to the sealing of the ghetto, then the annihilation of nearly all its residents. The exhibition is for the most part based on materials from the Ringelblum Archive. Most of the display materials are photographs and documents - there are very few three-dimensional artifacts from the ghetto since most everything in the Jewish quarter was destroyed. Click here ---->Exhibit<.---- to view more from the exhibit.

The exhibition includes documentary films that were made especially for the Institute. A 32 minute film about the Warsaw Ghetto is available in seven languages: Polish, English, Hebrew, German, French, Spanish, and Russian. It should be mentioned, that all the information placards on the exhibits are in both Polish and English, showing that they have directed their exhibit towards an international audience. The exhibition includes documentary films that were made especially for the Institute. A 32 minute film about the Warsaw Ghetto is available in seven languages: Polish, English, Hebrew, German, French, Spanish, and Russian. It should be mentioned, that all the information placards on the exhibits are in both Polish and English, showing that they have directed their exhibit towards an international audience.

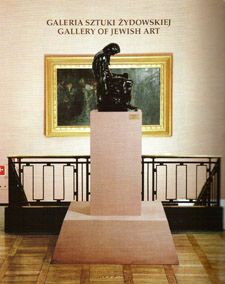

In the permanent art exhibition on the third floor, works of both Ashkenazi and Sephardic art are represented. The latter are items from Greek Jews who perished in the camps of Auschwitz and Majdanek. After the war, items were found in warehouses that had been used by the Germans. These include silver containers, candlesticks, lamps, and wine goblets. In the main exhibition room are paintings and sculptures, including pieces by some of the most important Jewish artists of the 19th century. This extraordinary exhibit of Jewish art and culture reflects the shared intent of other venues who believe that visitors can only appreciate the catastrophe of the Holocaust when they see and experience the extent of the culture lost. In the permanent art exhibition on the third floor, works of both Ashkenazi and Sephardic art are represented. The latter are items from Greek Jews who perished in the camps of Auschwitz and Majdanek. After the war, items were found in warehouses that had been used by the Germans. These include silver containers, candlesticks, lamps, and wine goblets. In the main exhibition room are paintings and sculptures, including pieces by some of the most important Jewish artists of the 19th century. This extraordinary exhibit of Jewish art and culture reflects the shared intent of other venues who believe that visitors can only appreciate the catastrophe of the Holocaust when they see and experience the extent of the culture lost.

Return to top of page

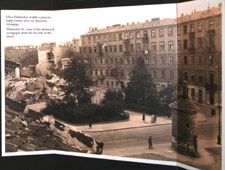

Upon our arrival in Warsaw, I was pleasantly surprised to see a beautiful, bustling rebuilt city, which bore little to no resemblance to the pictures of total destruction immediately following WWII. During the siege of Warsaw in the Invasion of Poland in 1939, about 1150 bombing sorties by German aircraft were flown on September 25th in an effort to terrorize the defenders into surrendering. Upon our arrival in Warsaw, I was pleasantly surprised to see a beautiful, bustling rebuilt city, which bore little to no resemblance to the pictures of total destruction immediately following WWII. During the siege of Warsaw in the Invasion of Poland in 1939, about 1150 bombing sorties by German aircraft were flown on September 25th in an effort to terrorize the defenders into surrendering.

500 tons of high explosive bombs and 72 tons of incendiary bombs were dropped on the city in all. The Germans did not hesitate to bomb civilian targets and hospitals marked with the Red Cross symbol. In the course of the war approximately 84 % of the city was destroyed largely due to German mass bombings but heavy artillery fire was also responsible. 500 tons of high explosive bombs and 72 tons of incendiary bombs were dropped on the city in all. The Germans did not hesitate to bomb civilian targets and hospitals marked with the Red Cross symbol. In the course of the war approximately 84 % of the city was destroyed largely due to German mass bombings but heavy artillery fire was also responsible.

Towards the end of 1940, an area in the central and northern part of the city was designated where all Jewish inhabitants were to be concentrated. Some 350,000 Jews lived in Warsaw prior to WWII, the majority occupying that part of the city where the ghetto was created. Jews who lived in other districts of Warsaw, as well as those who inhabited little towns and villages near the city, were forced to move into the Ghetto. Before the 1942 deportation to the death camp, Treblinka, more than 400,000 Jews were confined in the Warsaw Ghetto; by 1942, 1/3 of this number had died of starvation and disease. Once the whole population of the Ghetto was deported, the district encompassing some 750 acres was leveled to the ground. Towards the end of 1940, an area in the central and northern part of the city was designated where all Jewish inhabitants were to be concentrated. Some 350,000 Jews lived in Warsaw prior to WWII, the majority occupying that part of the city where the ghetto was created. Jews who lived in other districts of Warsaw, as well as those who inhabited little towns and villages near the city, were forced to move into the Ghetto. Before the 1942 deportation to the death camp, Treblinka, more than 400,000 Jews were confined in the Warsaw Ghetto; by 1942, 1/3 of this number had died of starvation and disease. Once the whole population of the Ghetto was deported, the district encompassing some 750 acres was leveled to the ground.

The Warsaw Ghetto Wall, which was about 10 feet high and 10 miles in total length, separated the Jewish district from the rest of the city. Any Jews outside of the ghetto could have only survived with help from the Poles. It is estimated that some 20,000 Warsaw Jews used that help and managed to survive the war in Nazi-occupied Warsaw. A piece of the Ghetto Wall is preserved in a courtyard between Zlota and Sienna Streets. Since the late 70’s local resident and army veteran Mieczyslaw Jedruszczak has fought to preserve the historical site from being a victim of urban expansion. The Warsaw Ghetto Wall, which was about 10 feet high and 10 miles in total length, separated the Jewish district from the rest of the city. Any Jews outside of the ghetto could have only survived with help from the Poles. It is estimated that some 20,000 Warsaw Jews used that help and managed to survive the war in Nazi-occupied Warsaw. A piece of the Ghetto Wall is preserved in a courtyard between Zlota and Sienna Streets. Since the late 70’s local resident and army veteran Mieczyslaw Jedruszczak has fought to preserve the historical site from being a victim of urban expansion.

In the summer of 1942, about 300,000 Jews were deported from Warsaw to Treblinka When reports of mass murder in the killing center leaked back to the Warsaw Ghetto, a surviving group of mostly young people formed an organization called the Z.O.B. (for the Polish name, Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa, which means Jewish Fighting Organization). The Z.O.B., led by 23-year-old Mordecai Anielewicz, issued a proclamation calling for the Jewish people to resist going to the railroad cars. In January 1943, Warsaw Ghetto Fighters fired upon German troops as they tried to round up another group of ghetto inhabitants for deportation. Fighters used a small supply of weapons that had been smuggled into the Ghetto. After a few days, the troops retreated. This small victory inspired the ghetto fighters to prepare for future resistance.

On April 19, 1943, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising began after German troops and police entered the ghetto to deport its surviving inhabitants. Seven hundred and fifty fighters fought the heavily armed and well-trained Germans. The Ghetto Fighters were able to hold out for nearly a month, but on May 16, 1943, the revolt ended. The Germans had slowly crushed the resistance. Of the more than 56,000 Jews captured, about 7,000 were shot, and the remainder were deported to killing centers or concentration camps.

The first WWII Memorial built in Warsaw in 1946 marked the 3rd anniversary of the Ghetto Uprising. The memorial by Lean Marek Suzin marks the spot where the armed confrontation began and faces what was once a gate into the Ghetto. A red sandstone disk tilts forward, facing the now nonexistent gate through which German tanks tried to enter the Ghetto. Over the years of urban renewal the former meaning of the site has been lost. Today erroneous interpretation claims it being in the form of a sewer entrance, like those used by Ghetto Fighters to escape the Ghetto. This kind of loss of meaning and interpretive distortion of a memorial is the fate all sites of commemoration face when several generations pass and urban legends begin to have more place in the public consciousness than the actual history itself. Questions hang in the air of how to preserve the historical accuracy of a site of commemoration as well as how do you revive the historical accuracy of a site that has been subjected to years of unchallenged erroneous promotion. The first WWII Memorial built in Warsaw in 1946 marked the 3rd anniversary of the Ghetto Uprising. The memorial by Lean Marek Suzin marks the spot where the armed confrontation began and faces what was once a gate into the Ghetto. A red sandstone disk tilts forward, facing the now nonexistent gate through which German tanks tried to enter the Ghetto. Over the years of urban renewal the former meaning of the site has been lost. Today erroneous interpretation claims it being in the form of a sewer entrance, like those used by Ghetto Fighters to escape the Ghetto. This kind of loss of meaning and interpretive distortion of a memorial is the fate all sites of commemoration face when several generations pass and urban legends begin to have more place in the public consciousness than the actual history itself. Questions hang in the air of how to preserve the historical accuracy of a site of commemoration as well as how do you revive the historical accuracy of a site that has been subjected to years of unchallenged erroneous promotion.

This famous Monument to the Ghetto Heroes, designed by Nathan Rapoport (b. 1911), was unveiled on April 19, 1948, in Warsaw, Poland. The central bronze panel depicts the men, women and children of the ghetto bearing arms in front of a backdrop of the burning Ghetto. Mordechai Anielewicz, the leader of the revolt, stands in the center of the figures to ignite the spirit of rebellion with the torch he clutches in his left hand. The stone used in this memorial was originally quarried for a Nazi victory monument. It has become the recognized icon of memorialization to the Ghetto Uprising, dwarfing all others. Its inscription, “The Jewish Nation – to its fighters and martyrs,” distinctly sent the message that the resistance and struggle are what one should remember from the story of the Ghetto, not the mass destruction of hundreds of thousands of Ghetto victims. This approach relegates mass murder to a secondary role ~ a minimized Polish role as accused Nazi collaborators. This famous Monument to the Ghetto Heroes, designed by Nathan Rapoport (b. 1911), was unveiled on April 19, 1948, in Warsaw, Poland. The central bronze panel depicts the men, women and children of the ghetto bearing arms in front of a backdrop of the burning Ghetto. Mordechai Anielewicz, the leader of the revolt, stands in the center of the figures to ignite the spirit of rebellion with the torch he clutches in his left hand. The stone used in this memorial was originally quarried for a Nazi victory monument. It has become the recognized icon of memorialization to the Ghetto Uprising, dwarfing all others. Its inscription, “The Jewish Nation – to its fighters and martyrs,” distinctly sent the message that the resistance and struggle are what one should remember from the story of the Ghetto, not the mass destruction of hundreds of thousands of Ghetto victims. This approach relegates mass murder to a secondary role ~ a minimized Polish role as accused Nazi collaborators.

18 Mila Street was the approximate site where Mordechai Anielewicz and the Jewish Fighter's Organization's command committed mass suicide rather than be captured by the Nazis. This memorial mound was erected on the site at a level equal to the level of the wartime rubble in the Ghetto. It is now a favorite spot for snow sledders in the winter. At the bottom of the steps, a marker in English compliments the original three languages of Polish, Yiddish, and Hebrew on the marker. The English reads: "Grave of the Fighters of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising built from the rubble of Mila Street, one of the liveliest streets of pre-war Jewish Warsaw. These ruins of the bunker at 18 Mila Street are the place of rest of the . . . 18 Mila Street was the approximate site where Mordechai Anielewicz and the Jewish Fighter's Organization's command committed mass suicide rather than be captured by the Nazis. This memorial mound was erected on the site at a level equal to the level of the wartime rubble in the Ghetto. It is now a favorite spot for snow sledders in the winter. At the bottom of the steps, a marker in English compliments the original three languages of Polish, Yiddish, and Hebrew on the marker. The English reads: "Grave of the Fighters of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising built from the rubble of Mila Street, one of the liveliest streets of pre-war Jewish Warsaw. These ruins of the bunker at 18 Mila Street are the place of rest of the . . .

. . . commanders and fighters of the Jewish Combat Organization as well as some civilians. Among them lies Mordechai Anielewicz, the commander in chief on May 18, 1943, surrounded by the Nazis after three weeks of struggle, many perished or took their own lives, refusing to perish at the hands of their enemies. There were several hundred bunkers built in the Ghetto, found and destroyed by the Nazis. They became graves. They could not save those who sought refuge inside them, yet they remain everlasting symbols of the Warsaw Jews' will to live. The bunker at Mila Street was the largest in the ghetto. It is the place of rest of over one hundred fighters, only some of whom are known by name. Here they rest, buried where they fell, to remind us that the whole earth is their grave." . . . commanders and fighters of the Jewish Combat Organization as well as some civilians. Among them lies Mordechai Anielewicz, the commander in chief on May 18, 1943, surrounded by the Nazis after three weeks of struggle, many perished or took their own lives, refusing to perish at the hands of their enemies. There were several hundred bunkers built in the Ghetto, found and destroyed by the Nazis. They became graves. They could not save those who sought refuge inside them, yet they remain everlasting symbols of the Warsaw Jews' will to live. The bunker at Mila Street was the largest in the ghetto. It is the place of rest of over one hundred fighters, only some of whom are known by name. Here they rest, buried where they fell, to remind us that the whole earth is their grave."

In 1983, as part of commemorative events for the 40th anniversary of the Uprising, the Polish Government gave official approval to the project titled Memorial Route of Jewish Martyrdom and Struggle, which was unveiled in 1988, on the 45th anniversary of the Ghetto Uprising. It consists of 19 one meter high, black stenite blocks spread out between the Rapoport Ghetto Fighter's Monument and the Umschlagplatz, the place of deportation; it also includes two commemorative plaques on the former buildings of SS headquarters and the Jewish hospital; and a new Umschlagplatz Memorial. Each block commemorates a person connected with the Ghetto, such as poets, fighters, or religious leaders. Walking this route and reading the memorial plaques allows visitors to experience a more personal touch of memorialization that gives names to victims and details of their fate, leading them to the new Umschlagplatz Memorial. In 1983, as part of commemorative events for the 40th anniversary of the Uprising, the Polish Government gave official approval to the project titled Memorial Route of Jewish Martyrdom and Struggle, which was unveiled in 1988, on the 45th anniversary of the Ghetto Uprising. It consists of 19 one meter high, black stenite blocks spread out between the Rapoport Ghetto Fighter's Monument and the Umschlagplatz, the place of deportation; it also includes two commemorative plaques on the former buildings of SS headquarters and the Jewish hospital; and a new Umschlagplatz Memorial. Each block commemorates a person connected with the Ghetto, such as poets, fighters, or religious leaders. Walking this route and reading the memorial plaques allows visitors to experience a more personal touch of memorialization that gives names to victims and details of their fate, leading them to the new Umschlagplatz Memorial.

The new Umschlagplatz Memorial, constructed in 1988, replaced the first Umschlagplatz Memorial Plaque that was placed on the wall of the loading dock railroad platform from which 350,000 Jews from the Ghetto were deported to Treblinka. It read in 3 languages: “This is the gate through which hundreds of thousands of Warsaw Jews, victims of Nazi genocide from 1942 to 1943, went to martyrs’ deaths in exterminations camps.” The new memorial is an enclosure in white marble, with a narrow entrance capped by a black bas-relief representing a forest of felled trees. Facing that entrance, a gap in the opposite wall opens up to a view of a living tree. On the inner walls of the memorial are engraved several hundred names of the first Ghetto victims deported to Treblinka. This is a distinct shift from the monumental heroic theme of Holocaust memory in Warsaw to a more human size personal connection. The new Umschlagplatz Memorial, constructed in 1988, replaced the first Umschlagplatz Memorial Plaque that was placed on the wall of the loading dock railroad platform from which 350,000 Jews from the Ghetto were deported to Treblinka. It read in 3 languages: “This is the gate through which hundreds of thousands of Warsaw Jews, victims of Nazi genocide from 1942 to 1943, went to martyrs’ deaths in exterminations camps.” The new memorial is an enclosure in white marble, with a narrow entrance capped by a black bas-relief representing a forest of felled trees. Facing that entrance, a gap in the opposite wall opens up to a view of a living tree. On the inner walls of the memorial are engraved several hundred names of the first Ghetto victims deported to Treblinka. This is a distinct shift from the monumental heroic theme of Holocaust memory in Warsaw to a more human size personal connection.

When entering the Jewish Okopoxa Cemetery in Warsaw, one immediately sees this restoration of the original gate of the Jewish Cemetery, renovated in 1998 by the Gesia Foundation, "In Honor of the late Moises Karwasser and in Eternal Memory of the Six Million Jews that were murdered by the Nazi Regime during the Holocaust. In celebration of their lives, we dedicate this gate - with the generous support of Arick and Lauren K. Karwasser and their children." Memorials by family members to Holocaust victims are prevalent on the grounds. When entering the Jewish Okopoxa Cemetery in Warsaw, one immediately sees this restoration of the original gate of the Jewish Cemetery, renovated in 1998 by the Gesia Foundation, "In Honor of the late Moises Karwasser and in Eternal Memory of the Six Million Jews that were murdered by the Nazi Regime during the Holocaust. In celebration of their lives, we dedicate this gate - with the generous support of Arick and Lauren K. Karwasser and their children." Memorials by family members to Holocaust victims are prevalent on the grounds.

This authentic reproduction of the Warsaw Ghetto Wall, also located in the cemetery, surrounds a memorial "to the one million Jewish Children murdered by Nazi German Barbarians, 1939-1945." The founder/sponsor of the memorial, Jack Eisner, posted his own original poetry on the left side of the monument: "Grandma Masha had twenty grandchildren. Grandma Hana had eleven. Only I survived." These brief words describe the tremendous loss of families that the survivors suffered. The Okopoxa Cemetery is the heart of Jewish life today, with its carefully preserved 100,000 tombstones. Here is buried the community that once was in addition to the mass graves of more than 100,000 of those who perished in the Ghetto. This authentic reproduction of the Warsaw Ghetto Wall, also located in the cemetery, surrounds a memorial "to the one million Jewish Children murdered by Nazi German Barbarians, 1939-1945." The founder/sponsor of the memorial, Jack Eisner, posted his own original poetry on the left side of the monument: "Grandma Masha had twenty grandchildren. Grandma Hana had eleven. Only I survived." These brief words describe the tremendous loss of families that the survivors suffered. The Okopoxa Cemetery is the heart of Jewish life today, with its carefully preserved 100,000 tombstones. Here is buried the community that once was in addition to the mass graves of more than 100,000 of those who perished in the Ghetto.

Janusz Korczak, a doctor, educator, and author of children's books, established and ran a Jewish orphanage in Warsaw. After declining offers to be rescued, he marched with his children to Umschlagplatz on August 5, 1942. He did not leave the Ghetto but rather stayed with his children until the very end. He boarded the train at the point of deportation and like thousands of other deportees from the Warsaw Ghetto, died in the gas chambers of Treblinka. This symbolic monument in the Okopoxa Cemetery in Warsaw stands unique, as there are few statues to individuals in the cemetery. Janusz Korczak is the only individual memorialized at the Treblinka Concentration Camp Memorial, where 17,000 granite shards are set in concrete around a 26 foot obelisk. Korczak's name is the only individual's name inscribed on one of the slabs while several hundred others bear names of Polish communities of Jews destroyed in the Shoah. Janusz Korczak, a doctor, educator, and author of children's books, established and ran a Jewish orphanage in Warsaw. After declining offers to be rescued, he marched with his children to Umschlagplatz on August 5, 1942. He did not leave the Ghetto but rather stayed with his children until the very end. He boarded the train at the point of deportation and like thousands of other deportees from the Warsaw Ghetto, died in the gas chambers of Treblinka. This symbolic monument in the Okopoxa Cemetery in Warsaw stands unique, as there are few statues to individuals in the cemetery. Janusz Korczak is the only individual memorialized at the Treblinka Concentration Camp Memorial, where 17,000 granite shards are set in concrete around a 26 foot obelisk. Korczak's name is the only individual's name inscribed on one of the slabs while several hundred others bear names of Polish communities of Jews destroyed in the Shoah.

In 1912, Korczak established a Jewish Orphanage, Dom Sierot, in this building which he designed to advance his progressive educational theories. He envisioned a world in which children structured their own world and became experts in their own matters. Jewish children between the ages of seven and fourteen were allowed to live here while attending Polish public school and government-sponsored Jewish schools, known as "Sabbath" schools. The orphanage opened a summer camp in 1921, which remained in operation until the summer of 1940. In 1912, Korczak established a Jewish Orphanage, Dom Sierot, in this building which he designed to advance his progressive educational theories. He envisioned a world in which children structured their own world and became experts in their own matters. Jewish children between the ages of seven and fourteen were allowed to live here while attending Polish public school and government-sponsored Jewish schools, known as "Sabbath" schools. The orphanage opened a summer camp in 1921, which remained in operation until the summer of 1940.

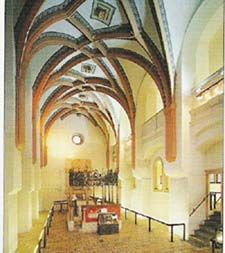

Besides serving as principal of Dom Sierot and another orphanage, Nasz Dom, Korczak was also a doctor and author, worked at a Polish radio station, was a principal of an experimental school, published a children’s newspaper and was a docent at a Polish university. Korczak also served as an expert witness in a district court for minors. He became well-known in Polish society and received many awards. The rise of anti-Semitism in the 1930's restricted only his activities with Jews. His life's story is exhibited through photographs and documents that encircle the main hall of his beautifully restored orphanage in Warsaw. Besides serving as principal of Dom Sierot and another orphanage, Nasz Dom, Korczak was also a doctor and author, worked at a Polish radio station, was a principal of an experimental school, published a children’s newspaper and was a docent at a Polish university. Korczak also served as an expert witness in a district court for minors. He became well-known in Polish society and received many awards. The rise of anti-Semitism in the 1930's restricted only his activities with Jews. His life's story is exhibited through photographs and documents that encircle the main hall of his beautifully restored orphanage in Warsaw.

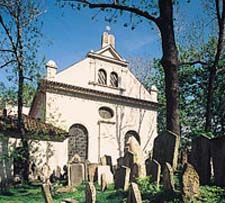

Founded in 1902 by Zalman Nozyk and his wife, the Nozyk Synagogue in Warsaw was devastated during World War II. During the occupation, the synagogue was used by the Nazis for a stable and fodder storage, thus causing considerable damage. Bombardments of the city during the Warsaw Uprising in 1944 caused severe damage to the roof and part of the elevation. It was renovated after the war and, with financial help from the Polish government, later reconstructed between 1977 and 1983. The Nozyk Synagogue still holds services on the Sabbath and Jewish holidays. To view a short video clip of the synagogue, click here ---->Nozyk<.----. Founded in 1902 by Zalman Nozyk and his wife, the Nozyk Synagogue in Warsaw was devastated during World War II. During the occupation, the synagogue was used by the Nazis for a stable and fodder storage, thus causing considerable damage. Bombardments of the city during the Warsaw Uprising in 1944 caused severe damage to the roof and part of the elevation. It was renovated after the war and, with financial help from the Polish government, later reconstructed between 1977 and 1983. The Nozyk Synagogue still holds services on the Sabbath and Jewish holidays. To view a short video clip of the synagogue, click here ---->Nozyk<.----.

The Nozyk Synagogue is located at number 6 Twarda Street in an area of Warsaw that was originally inside the Little Ghetto in 1940, but was later outside the Ghetto after it was made smaller, following deportations. The Nozyk Synagogue is the only synagogue in Warsaw that survived the war. This beautiful restored remnant of pre-WWII Jewish Warsaw is another reminder of the missing millions, many of whom filled this temple. Today there are only about 5,000 Jews living openly as Jews in Warsaw, mostly elderly, and also perhaps 20,000 to 50,000 hiding their Jewishness. Warsaw is now the city of monuments, built to the memory of its Jewish past that can never be reclaimed. Once a country sheltering the largest population of Jews in Europe, Poland became the harbinger of the Nazi death camps, the sites of devastating destruction of Eastern European Jewry. The following camps are presented below: Majdanek, Belzec, Auschwitz I, Auschwitz II Birkenau, Plaszow, and Theresienstadt, previously Terezin in the Czech Republic. The Nozyk Synagogue is located at number 6 Twarda Street in an area of Warsaw that was originally inside the Little Ghetto in 1940, but was later outside the Ghetto after it was made smaller, following deportations. The Nozyk Synagogue is the only synagogue in Warsaw that survived the war. This beautiful restored remnant of pre-WWII Jewish Warsaw is another reminder of the missing millions, many of whom filled this temple. Today there are only about 5,000 Jews living openly as Jews in Warsaw, mostly elderly, and also perhaps 20,000 to 50,000 hiding their Jewishness. Warsaw is now the city of monuments, built to the memory of its Jewish past that can never be reclaimed. Once a country sheltering the largest population of Jews in Europe, Poland became the harbinger of the Nazi death camps, the sites of devastating destruction of Eastern European Jewry. The following camps are presented below: Majdanek, Belzec, Auschwitz I, Auschwitz II Birkenau, Plaszow, and Theresienstadt, previously Terezin in the Czech Republic.

Return to top of page

At the end of July 1941, Heinrich Himmler decided on the foundation of a concentration camp in Lublin called, Majdanek, becoming the eastern most camp at that time.The early plans envisioned a camp size large enough to house 250,000 prisoners at one time. These grandiose plans were curtailed when German war difficulties arose resulting in only 1/5 of the original plans being realized between 1941 and 1944. The camp was composed of prisoner barracks, workshops, administration buildings, mass murder installations – gas chambers and crematorium, security-fencing, watchtowers, and sentry boxes. At the end of July 1941, Heinrich Himmler decided on the foundation of a concentration camp in Lublin called, Majdanek, becoming the eastern most camp at that time.The early plans envisioned a camp size large enough to house 250,000 prisoners at one time. These grandiose plans were curtailed when German war difficulties arose resulting in only 1/5 of the original plans being realized between 1941 and 1944. The camp was composed of prisoner barracks, workshops, administration buildings, mass murder installations – gas chambers and crematorium, security-fencing, watchtowers, and sentry boxes.

Like other concentration camps, Majdanek had its branch and subsidiary camps and labor detachments for work outside the camp. The first prisoners at Majdanek were Russian POWs brought from a camp in Chelm. From the early days of Majdanek, transports of prisoners were coming in from other camps – from Auschwitz, Dachau, Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald, Dora, Ravensbrück, Flossenbürg, and Neuengamme. At the turn of 1941-1942, Majdanek became the center of detention for Jews from Lublin and its surrounding areas. Transports of Jews on a massive scale then began arriving in April 1942, first from Slovakia and the Czech Republic and then from other countries: Austria, Germany, France, Belgium, and Holland. From mid 1942 to mid 1943 transports from the Ghettos in Lublin, Warsaw, and Bialystok predominated. For them, Majdanek was both a concentration camp and a death camp. Like other concentration camps, Majdanek had its branch and subsidiary camps and labor detachments for work outside the camp. The first prisoners at Majdanek were Russian POWs brought from a camp in Chelm. From the early days of Majdanek, transports of prisoners were coming in from other camps – from Auschwitz, Dachau, Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald, Dora, Ravensbrück, Flossenbürg, and Neuengamme. At the turn of 1941-1942, Majdanek became the center of detention for Jews from Lublin and its surrounding areas. Transports of Jews on a massive scale then began arriving in April 1942, first from Slovakia and the Czech Republic and then from other countries: Austria, Germany, France, Belgium, and Holland. From mid 1942 to mid 1943 transports from the Ghettos in Lublin, Warsaw, and Bialystok predominated. For them, Majdanek was both a concentration camp and a death camp.

Overall, there were about 300,000 prisoners brought to Majdanek of over 50 nationalities. Jews constituted the most numerous group there, 41%, Polish prisoners coming in second, 35%. In Majdanek, there was no continuous numeration as in other camps, but rather a rotation of numbers. When the figure reached 20,000, the newcomers received the numbers left vacant by the dead or those released from the camp. In addition, markings were used to show the reason of imprisonment and the nationality. This was accomplished by the infamous triangles of different colors, seen here in a display case in one of the exhibit barracks. Overall, there were about 300,000 prisoners brought to Majdanek of over 50 nationalities. Jews constituted the most numerous group there, 41%, Polish prisoners coming in second, 35%. In Majdanek, there was no continuous numeration as in other camps, but rather a rotation of numbers. When the figure reached 20,000, the newcomers received the numbers left vacant by the dead or those released from the camp. In addition, markings were used to show the reason of imprisonment and the nationality. This was accomplished by the infamous triangles of different colors, seen here in a display case in one of the exhibit barracks.

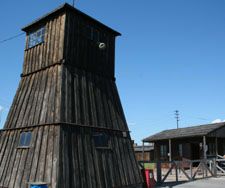

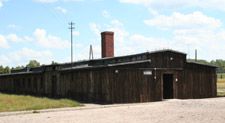

Prisoner barracks divided into fields were the central part of the camp. Each field was a rectangle surrounded by a double line of barbed wire fence equipped with high voltage installations. Around the 6 fields were raised 18 watchtowers where the SS stood on duty day and night. Every field had 24 barracks in two rows with a roll call square and a gallows in the middle. Outside the rectangle of the fields stood mass murder installations, workshops and storage barracks, SS living quarters and the commandant’s lodgings. Prisoner barracks divided into fields were the central part of the camp. Each field was a rectangle surrounded by a double line of barbed wire fence equipped with high voltage installations. Around the 6 fields were raised 18 watchtowers where the SS stood on duty day and night. Every field had 24 barracks in two rows with a roll call square and a gallows in the middle. Outside the rectangle of the fields stood mass murder installations, workshops and storage barracks, SS living quarters and the commandant’s lodgings.

The decision to set up a Museum at Majdanek was made as early as the autumn of 1944 with the organization of the Society for the Preservation of Majdanek. Visitations began in November 1944 and it was the first museum to operate on the site of a former camp. The main aims of the museum are: maintain and manage the area of the former camp, with its buildings and installations; collect and research the relics of the camp and archive materials documenting its history; research the problems that refer to the camp; disseminate knowledge on Majdanek by means of exhibitions, publications, and educational projects; collect art on anti-war themes and exhibit it; and utilize the tragic experiences of the past for education in the spirit of unity between nations. The decision to set up a Museum at Majdanek was made as early as the autumn of 1944 with the organization of the Society for the Preservation of Majdanek. Visitations began in November 1944 and it was the first museum to operate on the site of a former camp. The main aims of the museum are: maintain and manage the area of the former camp, with its buildings and installations; collect and research the relics of the camp and archive materials documenting its history; research the problems that refer to the camp; disseminate knowledge on Majdanek by means of exhibitions, publications, and educational projects; collect art on anti-war themes and exhibit it; and utilize the tragic experiences of the past for education in the spirit of unity between nations.

At the site of the former camp today are preserved the barracks in Field III, fencing of five fields and the watchtowers. Also still standing are the gas chambers next to Field I and the reconstructed crematorium beyond Field V. Most of the workshops built along side the road way are used today as exhibition areas. The area of the former camp and all that remained of the camp site were given over to the State Museum of Majdanek by the Republic of Poland on July 2, 1947 so that it could be preserved for all times as the Monument to Martyrdom. At the site of the former camp today are preserved the barracks in Field III, fencing of five fields and the watchtowers. Also still standing are the gas chambers next to Field I and the reconstructed crematorium beyond Field V. Most of the workshops built along side the road way are used today as exhibition areas. The area of the former camp and all that remained of the camp site were given over to the State Museum of Majdanek by the Republic of Poland on July 2, 1947 so that it could be preserved for all times as the Monument to Martyrdom.

During its years of operation, the living conditions at Majdanek were primitive at best. The thin cotton striped uniforms provided no protection from the rain and snow and inmates remained wet and often froze to death. In the early years of the camp, prisoners slept on straw spread over bare ground. Later, floors were put in and three-tier plank beds without mattresses were filled with straw and wood shavings instead. Typhoid epidemics, diarrhea, tuberculosis, dysentery, scurvy, scabies and mental disorders raged due to the ever deteriorating sanitary conditions, malnutrition, lice, and rodents. During its years of operation, the living conditions at Majdanek were primitive at best. The thin cotton striped uniforms provided no protection from the rain and snow and inmates remained wet and often froze to death. In the early years of the camp, prisoners slept on straw spread over bare ground. Later, floors were put in and three-tier plank beds without mattresses were filled with straw and wood shavings instead. Typhoid epidemics, diarrhea, tuberculosis, dysentery, scurvy, scabies and mental disorders raged due to the ever deteriorating sanitary conditions, malnutrition, lice, and rodents.

Prisoners were exposed not only to accelerated “natural” death, but also experienced direct genocide in the forms of executions and gassings on a mass scale. Gas chambers were in use at Majdanek from mid 1942. Over the entrance door it read “Bath and Disinfection” to lull the victims into compliance. Prisoners were exposed not only to accelerated “natural” death, but also experienced direct genocide in the forms of executions and gassings on a mass scale. Gas chambers were in use at Majdanek from mid 1942. Over the entrance door it read “Bath and Disinfection” to lull the victims into compliance.

The victims were mainly Jews selected for death directly upon arrival. Other forms of executions were hanging, clubbing and beatings, strangulation, and drowning in water reservoirs and cesspits. Of the 235,000 victims of Majdanek, 48% were Jews, 31% were Poles, 16% were from the Soviet Union, and the remainder came from all other nationalities. The victims were mainly Jews selected for death directly upon arrival. Other forms of executions were hanging, clubbing and beatings, strangulation, and drowning in water reservoirs and cesspits. Of the 235,000 victims of Majdanek, 48% were Jews, 31% were Poles, 16% were from the Soviet Union, and the remainder came from all other nationalities.

These walls bear witness to the use of Zyklon- B for exterminations in the blue stains from the crystals embedded in the sides of the walls. This reinforced concrete chamber also used carbon monoxide, a gas that was supplied by means of a conduit from the SS guard booth. The first corpses were buried in collective graves and from mid 1942 they were burned in the crematorium and on pyres. These walls bear witness to the use of Zyklon- B for exterminations in the blue stains from the crystals embedded in the sides of the walls. This reinforced concrete chamber also used carbon monoxide, a gas that was supplied by means of a conduit from the SS guard booth. The first corpses were buried in collective graves and from mid 1942 they were burned in the crematorium and on pyres.

In the first crematorium, two furnaces burning crude oil had a capacity of 200 bodies per day. To facilitate greater numbers of bodies burning hotter and faster, this new crematorium, designed by the Berlin firm of K. Kori, had five stoves and burned coal. Of the 300,000 prisoners interned at Majdanek, 235,000 died at Majdanek. 45,000 were transferred to other camps, 20,000 were released, and only 1500 were liberated. In the first crematorium, two furnaces burning crude oil had a capacity of 200 bodies per day. To facilitate greater numbers of bodies burning hotter and faster, this new crematorium, designed by the Berlin firm of K. Kori, had five stoves and burned coal. Of the 300,000 prisoners interned at Majdanek, 235,000 died at Majdanek. 45,000 were transferred to other camps, 20,000 were released, and only 1500 were liberated.

This building, which houses the ovens above, is a reconstruction for site preservation purposes. The original crematoriums were set afire by the Germans when they abandoned the camp to the advancing Soviet army. The original brick ovens were restored and the wooden structure rebuilt. Curators felt it important to portray the crematorium that had incinerated thousands of Majdanek victims in its original setting. This building, which houses the ovens above, is a reconstruction for site preservation purposes. The original crematoriums were set afire by the Germans when they abandoned the camp to the advancing Soviet army. The original brick ovens were restored and the wooden structure rebuilt. Curators felt it important to portray the crematorium that had incinerated thousands of Majdanek victims in its original setting.

The largest single execution took place on November 3, 1943, when 18,000 Jews were shot. The mass shooting was the final stage in the liquidation of Jews in Lublin. Three rows of deep ditches had been dug near the crematorium. Taken to the ditches and stripped naked, victims had to lie down in the ditches and the SS machine-gunned them from the top of the ditch. Others then had to line up, lie down on top of the corpses and then were shot in the same manner. The shooting of rows and rows of inmates continued until the ditches were filled to the brim. The action lasted without break from morning till evening, while music played from car radios equipped with loud speakers, to deaden the cacophony of the crime. The corpses were incinerated on pyres arranged on the iron chassis of old lorries. The human ashes that remained were mixed with kitchen scraps and earth to make compost and then used as fertilizer in the fields and gardens of the camp. The largest single execution took place on November 3, 1943, when 18,000 Jews were shot. The mass shooting was the final stage in the liquidation of Jews in Lublin. Three rows of deep ditches had been dug near the crematorium. Taken to the ditches and stripped naked, victims had to lie down in the ditches and the SS machine-gunned them from the top of the ditch. Others then had to line up, lie down on top of the corpses and then were shot in the same manner. The shooting of rows and rows of inmates continued until the ditches were filled to the brim. The action lasted without break from morning till evening, while music played from car radios equipped with loud speakers, to deaden the cacophony of the crime. The corpses were incinerated on pyres arranged on the iron chassis of old lorries. The human ashes that remained were mixed with kitchen scraps and earth to make compost and then used as fertilizer in the fields and gardens of the camp.

After liberation, mounds of human compost still remained and have been enshrined in the Memorial Mausoleum built on the site of the execution ditches. In 1969 two monumental structures were erected that made up the Monument of Struggle and Martyrdom and the Mausoleum. The Monument looms at one end of the Road of Homage and the Mausoleum hovers at the other. The Mausoleum is a huge circular urn with a Dome resting on columns containing the ashes of murdered victims. After liberation, mounds of human compost still remained and have been enshrined in the Memorial Mausoleum built on the site of the execution ditches. In 1969 two monumental structures were erected that made up the Monument of Struggle and Martyrdom and the Mausoleum. The Monument looms at one end of the Road of Homage and the Mausoleum hovers at the other. The Mausoleum is a huge circular urn with a Dome resting on columns containing the ashes of murdered victims.

An inscription reads: “Let our fate be a warning to you.” In this picture, you can see the rising mound of human mulch in the center of the structure. There is no other site of Holocaust memorialization that had quite the same impact on my sensibilities as did seeing this huge mound of human dust. An inscription reads: “Let our fate be a warning to you.” In this picture, you can see the rising mound of human mulch in the center of the structure. There is no other site of Holocaust memorialization that had quite the same impact on my sensibilities as did seeing this huge mound of human dust.

The Monument of Struggle and Martyrdom appears as a colossal gate made of stone and concrete that marks the entrance to the Majdanek Concentration Camp site. Majdanek was the first Nazi concentration / death camp I had ever visited and its impact on me was massive, much like this huge monument - indefinable, unexplainable, yet very, VERY real. The Monument of Struggle and Martyrdom appears as a colossal gate made of stone and concrete that marks the entrance to the Majdanek Concentration Camp site. Majdanek was the first Nazi concentration / death camp I had ever visited and its impact on me was massive, much like this huge monument - indefinable, unexplainable, yet very, VERY real.

Return to top of page

Immediately following the decision of the Nazis to implement “Aktion Reinhardt,” the Germans began construction of three death camps in Poland designed for the purpose of exterminating the Jews living in the region known as the “General -Gouvernement.” On November 1, 1941, Belzec, the first of the three death camps, the others being Treblinka and Sobibor, was the first death camp in which the Nazis used stationary gas chambers for killing their victims. The annihilation of the Jews at Belzec lasted for only nine months between March and December of 1942, but in that time over ½ a million exterminations took place, mostly Polish and foreign Jews, and small groups of non-Jewish Poles and Gypsies. Corpses were buried in about 30 mass graves located within the perimeter of the camp site, which was at most 400 meters square. It was this practice of mass burials within the camp areas itself that caused the Germans to abandon the camp when the Fall and Winter weather caused the bodies of the buried to swell and literally push themselves up out of the ground. This presented great health dangers for the perpetrators. When cremation pyres could not incinerate the bodies fast enough, abandonment was the only "healthy" alternative for the camp personnel. Immediately following the decision of the Nazis to implement “Aktion Reinhardt,” the Germans began construction of three death camps in Poland designed for the purpose of exterminating the Jews living in the region known as the “General -Gouvernement.” On November 1, 1941, Belzec, the first of the three death camps, the others being Treblinka and Sobibor, was the first death camp in which the Nazis used stationary gas chambers for killing their victims. The annihilation of the Jews at Belzec lasted for only nine months between March and December of 1942, but in that time over ½ a million exterminations took place, mostly Polish and foreign Jews, and small groups of non-Jewish Poles and Gypsies. Corpses were buried in about 30 mass graves located within the perimeter of the camp site, which was at most 400 meters square. It was this practice of mass burials within the camp areas itself that caused the Germans to abandon the camp when the Fall and Winter weather caused the bodies of the buried to swell and literally push themselves up out of the ground. This presented great health dangers for the perpetrators. When cremation pyres could not incinerate the bodies fast enough, abandonment was the only "healthy" alternative for the camp personnel.

For many years Belzec was the most forgotten camp of the Holocaust. The New Memorial at the site of the camp was designed by Andrzej Solyga, Zdzislaw Pidek, and Marcin Roszczyk and opened on June 3, 2004 as a joint project of the American Jewish Committee and the Council for the Protection of the Memory of Combat and Martyrdom in Warsaw. Alan Elsner, journalist and grandson of victims killed at Belzec, can be credited with exposing the disgraceful neglect of the site after his visit to the old memorial in 1993. His reporting prompted the campaign that built this new memorial. I recommend all readers to link to his website, ---->Alan Elsner<.---- where you can read his article about the prior conditions of the site. The complex consists of a memorial to the victims of the camp, a reconstruction of an extermination pyre, and a museum with an exhibition about the history of the Belzec death camp. Click here ----> Belzec Video <.---- to view video clips of the Belzec Memorial site. For many years Belzec was the most forgotten camp of the Holocaust. The New Memorial at the site of the camp was designed by Andrzej Solyga, Zdzislaw Pidek, and Marcin Roszczyk and opened on June 3, 2004 as a joint project of the American Jewish Committee and the Council for the Protection of the Memory of Combat and Martyrdom in Warsaw. Alan Elsner, journalist and grandson of victims killed at Belzec, can be credited with exposing the disgraceful neglect of the site after his visit to the old memorial in 1993. His reporting prompted the campaign that built this new memorial. I recommend all readers to link to his website, ---->Alan Elsner<.---- where you can read his article about the prior conditions of the site. The complex consists of a memorial to the victims of the camp, a reconstruction of an extermination pyre, and a museum with an exhibition about the history of the Belzec death camp. Click here ----> Belzec Video <.---- to view video clips of the Belzec Memorial site.

A huge field of randomly sized concrete rubble covers the entire camp area of Belzec, with the center path through the site being reminiscent of “Die Schleuse,” (The Sluice) a camouflaged barbed wire path that led from the undressing and barber barracks straight to the gas chambers, which were also camouflaged with netting on raised poles. A huge field of randomly sized concrete rubble covers the entire camp area of Belzec, with the center path through the site being reminiscent of “Die Schleuse,” (The Sluice) a camouflaged barbed wire path that led from the undressing and barber barracks straight to the gas chambers, which were also camouflaged with netting on raised poles.

The darkly colored areas of the concrete rubble field demarcate the locations of the mass graves. In earlier years, a sculpture had been erected in the 1960s by the former Communist authorities of Poland. Jewish visitors to the site had complained that it was badly neglected, overgrown with weeds and strewn with garbage. They also said the existing memorial was inappropriate and was falling apart. A Polish team then carried out the most comprehensive archeological survey ever conducted on a major Holocaust site and located 33 previously unknown mass graves. According to reports, the survey team bored holes to a depth of 18 feet at 15-yard intervals throughout the site. The darkly colored areas of the concrete rubble field demarcate the locations of the mass graves. In earlier years, a sculpture had been erected in the 1960s by the former Communist authorities of Poland. Jewish visitors to the site had complained that it was badly neglected, overgrown with weeds and strewn with garbage. They also said the existing memorial was inappropriate and was falling apart. A Polish team then carried out the most comprehensive archeological survey ever conducted on a major Holocaust site and located 33 previously unknown mass graves. According to reports, the survey team bored holes to a depth of 18 feet at 15-yard intervals throughout the site.

"The largest mass graves ... contained unburned human remains (parts and pieces of skulls with hair and skin attached). The bottom layer of the graves consisted of several inches thick of black human fat. One grave contained uncrushed human bones so closely packed that the drill could not penetrate," wrote Robin O'Neill, member of the survey team. "The largest mass graves ... contained unburned human remains (parts and pieces of skulls with hair and skin attached). The bottom layer of the graves consisted of several inches thick of black human fat. One grave contained uncrushed human bones so closely packed that the drill could not penetrate," wrote Robin O'Neill, member of the survey team.

The Nazis had built Belzec to destroy the centuries-old Jewish communities of southern and eastern Poland. In 1942, with that job completed, the Nazis closed the camp.They later tried to hide their crime, burning the bodies and grinding up the bones.The memorial path that completely encircles the entire site bears the names of all the communities of Jewish victims that were murdered at Belzec. The Nazis had built Belzec to destroy the centuries-old Jewish communities of southern and eastern Poland. In 1942, with that job completed, the Nazis closed the camp.They later tried to hide their crime, burning the bodies and grinding up the bones.The memorial path that completely encircles the entire site bears the names of all the communities of Jewish victims that were murdered at Belzec.

The Interstice cuts through the earth, showing that the camp was built on a slope. The path leading to the granite wall is 600 feet long and the cut through the earth is 30 feet deep. The remains of thousands of unburned bodies were found. Out of respect for the dead, the graves were not opened and the bodies were not exhumed, so no identification was made. Knowing that you are walking through the site of mass graves is one of the more powerful effects of the new memorial at Belzec. The Interstice cuts through the earth, showing that the camp was built on a slope. The path leading to the granite wall is 600 feet long and the cut through the earth is 30 feet deep. The remains of thousands of unburned bodies were found. Out of respect for the dead, the graves were not opened and the bodies were not exhumed, so no identification was made. Knowing that you are walking through the site of mass graves is one of the more powerful effects of the new memorial at Belzec.

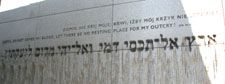

When you get to the end of the path, there is this inscription from The Tanakh, from the Book of Job, in Hebrew, Polish and English: "Earth, do not cover my blood; Let there be no resting place for my outcry." Job 16:18. When you get to the end of the path, there is this inscription from The Tanakh, from the Book of Job, in Hebrew, Polish and English: "Earth, do not cover my blood; Let there be no resting place for my outcry." Job 16:18.

This view is taken from the very farthest back edge of the site, looking down towards the entry and the Belzec Museum that is to your right when you enter the site. The camp seemed both small and confined and yet enormously huge at the same time. I found this abstracted portrayal of Holocaust history to have a powerful effect- every bit as powerful as seeing actual sites, as at Majdanek. This view is taken from the very farthest back edge of the site, looking down towards the entry and the Belzec Museum that is to your right when you enter the site. The camp seemed both small and confined and yet enormously huge at the same time. I found this abstracted portrayal of Holocaust history to have a powerful effect- every bit as powerful as seeing actual sites, as at Majdanek.

The entrance to the museum duplicates the entrance through the center of the camp, in that you descend into the museum, just as you walked down into the mass grave area of the concrete field. Photographs of families and children, laughing and smiling, tell of Jewish life before the Holocaust. This small museum houses only a few artifacts from the camp, with photographs from Nazi records that tell of the existence of the camp. The entrance to the museum duplicates the entrance through the center of the camp, in that you descend into the museum, just as you walked down into the mass grave area of the concrete field. Photographs of families and children, laughing and smiling, tell of Jewish life before the Holocaust. This small museum houses only a few artifacts from the camp, with photographs from Nazi records that tell of the existence of the camp.

Between December 1942 and April 1943, transports stopped arriving at the camp and during these months, Jewish prisoners had to open the mass graves and burn the bodies of the gassed victims on huge pyres of layered railroad ties. In June 1943, the camp was totally liquidated and all the buildings were destroyed. No significant physical evidence of the victims was ever to be found at the site and the transport lists were also destroyed. The victims of Belzec died in an anonymous mass and only two official survivors of the camp lived to provide post-war testimonies of life and death at Belzec. Between December 1942 and April 1943, transports stopped arriving at the camp and during these months, Jewish prisoners had to open the mass graves and burn the bodies of the gassed victims on huge pyres of layered railroad ties. In June 1943, the camp was totally liquidated and all the buildings were destroyed. No significant physical evidence of the victims was ever to be found at the site and the transport lists were also destroyed. The victims of Belzec died in an anonymous mass and only two official survivors of the camp lived to provide post-war testimonies of life and death at Belzec.

In the area of the rail ramps where the train cars stopped to unload their human cargo, stands a memorial fashioned after the pyres that were constructed for the burning of the corpses from the mass graves. I was impressed and touched by this memorial site, and felt I had made only a brief connection to the enormity of Belzec's atrocities. In the area of the rail ramps where the train cars stopped to unload their human cargo, stands a memorial fashioned after the pyres that were constructed for the burning of the corpses from the mass graves. I was impressed and touched by this memorial site, and felt I had made only a brief connection to the enormity of Belzec's atrocities.

Return to top of page

Auschwitz (main camp pictured here) has come to be recognized as the symbol of the Holocaust - the largest and most deadly of all 7000+ camps throughout Europe. The Nazis opened it in 1940 on the outskirts of the Polish city of Oswiecim, which came under German occupation during WWII. The Germans changed the name of the city to "Auschwitz," and this also became the name of the camp. Over the following years, the camp expanded until it comprised three main parts: Auschwitz I, Auschwitz II-Birkenau, and Auschwitz III-Monowitz, along with its 40 sub-camps. At first a place of imprisonment for the Poles and then Soviet POWs, beginning in 1942 the camp became the scene of the largest mass murder in human history, committed against the Jews deported to Auschwitz. It is estimated that the Nazis sent 1.3 million victims to Auschwitz, with at least 1,100,000 of them being Jews from all over Nazi occupied Europe, who were then mercilessly murdered. In an effort to remove the evidence of their crimes, the SS began dismantling or demolishing the gas chambers and the crematoria at Birkenau, along with other buildings at the end of the war. They also burned the records. Nazis then evacuated prisoners capable of walking into the heart of the Third Reich, with many dying on these death marches. Soviet Army soldiers liberated the remaining Auschwitz prisoners, around 7,000, in January 1945. Auschwitz (main camp pictured here) has come to be recognized as the symbol of the Holocaust - the largest and most deadly of all 7000+ camps throughout Europe. The Nazis opened it in 1940 on the outskirts of the Polish city of Oswiecim, which came under German occupation during WWII. The Germans changed the name of the city to "Auschwitz," and this also became the name of the camp. Over the following years, the camp expanded until it comprised three main parts: Auschwitz I, Auschwitz II-Birkenau, and Auschwitz III-Monowitz, along with its 40 sub-camps. At first a place of imprisonment for the Poles and then Soviet POWs, beginning in 1942 the camp became the scene of the largest mass murder in human history, committed against the Jews deported to Auschwitz. It is estimated that the Nazis sent 1.3 million victims to Auschwitz, with at least 1,100,000 of them being Jews from all over Nazi occupied Europe, who were then mercilessly murdered. In an effort to remove the evidence of their crimes, the SS began dismantling or demolishing the gas chambers and the crematoria at Birkenau, along with other buildings at the end of the war. They also burned the records. Nazis then evacuated prisoners capable of walking into the heart of the Third Reich, with many dying on these death marches. Soviet Army soldiers liberated the remaining Auschwitz prisoners, around 7,000, in January 1945.

(Auschwitz II - Birkenau pictured here) Several months after the war, a group of Polish prisoners, who had survived Auschwitz, began communicating the idea of commemorating the victims of the largest of the death camps. In April 1946, a group of Polish survivors arrived at the site of the camp with the intention of opening a museum. Thousands of visitors had begun arriving on a mass scale to search for traces of relatives or to pay homage to those who had been murdered. Survivors began acting as unofficial docents to these modern day pilgrims. On July 2, 1947 the Polish Parliament passed a law securing the grounds and buildings of Auschwitz as a place of international martyrdom and calling into being the Oswiecim-Brzezinka State Museum for this purpose.The museum's mission was to secure the grounds and buildings of the camp, and to collect and gather evidence and material related to the Nazi crimes so that they could be studied and made accessible to the public. There are 154 original camp buildings of various sorts in the Museum and Memorial, 56 at Auschwitz I and 98 at Birkenau. These include prisoner blocks and barracks, administration buildings, SS guardhouses, guard towers, and the camp gates. There are also 300 ruins, including the ruins of the gas chambers and crematoria at Birkenau, camp fences, paved roads, and train tracks. Thousands of objects belonging to the camp inmates were found at the site, including suitcases, Jewish prayer garments, artifical limbs, eyeglasses, shoes, and human hair. These objects make up a basic part of the Museum holdings and are on display in the exhibit rooms, housed in the brick barracks of Auschwitz I. Also on exhibit are hundreds of smaller items, such as umbrellas, combs, shaving brushes, toothbrushes, etc. The Museum encompasses 6,000 exhibits, including 2,000 works of art done in the camp by prisoners, often illegally, as well as other works of art produced after the war. The Archives contain a vast collection of Nazi documents, as well as material from the prisoner resistance movement, postwar accounts, memoirs, depositions, films, etc. (Auschwitz II - Birkenau pictured here) Several months after the war, a group of Polish prisoners, who had survived Auschwitz, began communicating the idea of commemorating the victims of the largest of the death camps. In April 1946, a group of Polish survivors arrived at the site of the camp with the intention of opening a museum. Thousands of visitors had begun arriving on a mass scale to search for traces of relatives or to pay homage to those who had been murdered. Survivors began acting as unofficial docents to these modern day pilgrims. On July 2, 1947 the Polish Parliament passed a law securing the grounds and buildings of Auschwitz as a place of international martyrdom and calling into being the Oswiecim-Brzezinka State Museum for this purpose.The museum's mission was to secure the grounds and buildings of the camp, and to collect and gather evidence and material related to the Nazi crimes so that they could be studied and made accessible to the public. There are 154 original camp buildings of various sorts in the Museum and Memorial, 56 at Auschwitz I and 98 at Birkenau. These include prisoner blocks and barracks, administration buildings, SS guardhouses, guard towers, and the camp gates. There are also 300 ruins, including the ruins of the gas chambers and crematoria at Birkenau, camp fences, paved roads, and train tracks. Thousands of objects belonging to the camp inmates were found at the site, including suitcases, Jewish prayer garments, artifical limbs, eyeglasses, shoes, and human hair. These objects make up a basic part of the Museum holdings and are on display in the exhibit rooms, housed in the brick barracks of Auschwitz I. Also on exhibit are hundreds of smaller items, such as umbrellas, combs, shaving brushes, toothbrushes, etc. The Museum encompasses 6,000 exhibits, including 2,000 works of art done in the camp by prisoners, often illegally, as well as other works of art produced after the war. The Archives contain a vast collection of Nazi documents, as well as material from the prisoner resistance movement, postwar accounts, memoirs, depositions, films, etc.

In addition to preservation work, the Museum carries out scholarly research, organizes exhibits, issues its own publications, organizes lectures, conferences, seminars, and symposia for teachers and students, and offers postgraduate course work for education on Totalitarianism, Nazism, and the Holocaust. But the most popular education is carried out among the visitors to the Auschwitz Memorial. An average of 1/2 million people visit Auschwitz every year. This is the most recognized venue and the most publicly witnessed legacy of the Holocaust, therefore it has the greatest impact on the manner is which Holocaust memory will be held in perpetuity. As the methodology of memorialization advances, both in theory and in practice, Auschwitz continues to generate not only admiration for its preservation work, but criticism for its manner and message of commemoration, produced for mass public appeal, often times seen as fulfilling a tourist appeal at the expense of historical analysis. In addition to preservation work, the Museum carries out scholarly research, organizes exhibits, issues its own publications, organizes lectures, conferences, seminars, and symposia for teachers and students, and offers postgraduate course work for education on Totalitarianism, Nazism, and the Holocaust. But the most popular education is carried out among the visitors to the Auschwitz Memorial. An average of 1/2 million people visit Auschwitz every year. This is the most recognized venue and the most publicly witnessed legacy of the Holocaust, therefore it has the greatest impact on the manner is which Holocaust memory will be held in perpetuity. As the methodology of memorialization advances, both in theory and in practice, Auschwitz continues to generate not only admiration for its preservation work, but criticism for its manner and message of commemoration, produced for mass public appeal, often times seen as fulfilling a tourist appeal at the expense of historical analysis.

The entrance to Auschwitz I, the gate with the infamous inscription, "Arbeit Macht Frei" (work makes you free), appeared as a cruel joke by its inmates. The camp originally had been the barracks of the Polish army, who had abandoned it at the outbreak of WWII. The entrance to Auschwitz I, the gate with the infamous inscription, "Arbeit Macht Frei" (work makes you free), appeared as a cruel joke by its inmates. The camp originally had been the barracks of the Polish army, who had abandoned it at the outbreak of WWII.